The Wall Street Journal - September 11, 2011, 4:33 p.m. ET

In Fracking's Wake

Some companies love that dirty water, because it means more money for cleaning it up

BY THE TRUCKLOAD With fracking's growth, tankers unloading wastewater keep a Texas recycling site busy

The growing volume of dirty water produced in shale-gas drilling has triggered a gold rush among water-treatment companies.

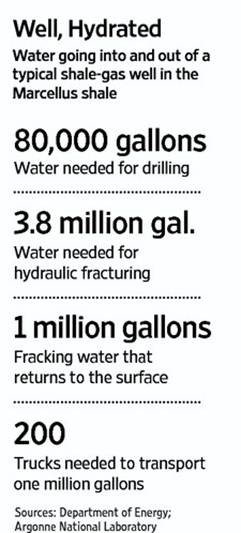

Energy companies increasingly are drilling for natural gas using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. In this process, water mixed with sand and chemicals is pumped into a well under high pressure; the mixture fractures the rock, allowing the gas to escape. Huge amounts of water are used, and about 10% to 40% of it emerges after a frack job, laced with a variety of contaminants.

Even as the volume of dirty water grows, the traditional methods of disposal are narrowing. Several states are considering or have recently imposed limits on wastewater disposal underground or in streams. Meanwhile, record drought in some drilling areas is making access to fresh water for drilling more difficult, costly and unpopular.

The net result: "For the first time there's a strong driver for technology" to clean up the wastewater from mines so it can be reused, says Laura Shenkar, founder of the Artemis Project, a water-technology consulting firm. Dozens of water-treatment companies have started up in the past year or so, and many of the more established companies are adapting their techniques for use in the shale-gas industry. How many of those companies the market can support remains to be seen.

Plenty of Options

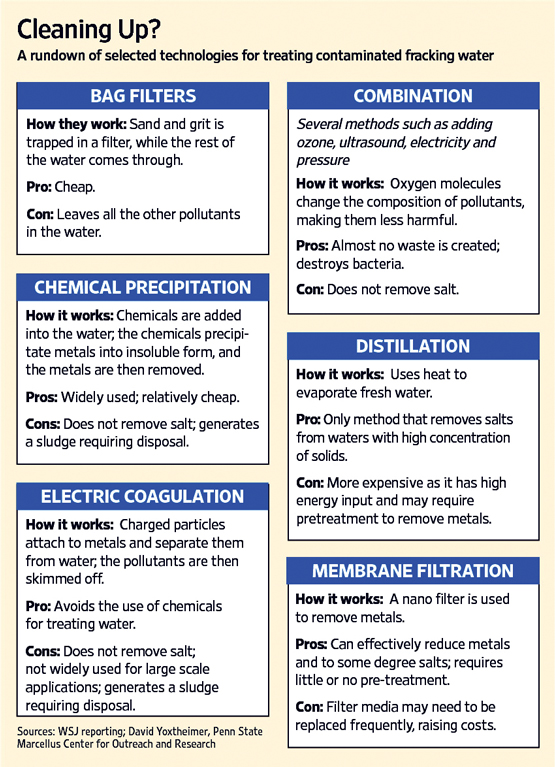

Companies are using several different approaches to shale-gas wastewater treatment.

|

|

Ecosphere Technologies Inc., based in Stuart, Fla., is one of the dominant providers of water treatment for the shale-gas industry, according to Lux Research, a technology research and consulting firm. The company's technology avoids the use of chemicals typically employed to treat wastewater. Ecosphere's process forces dirty water through pipes where ozone breaks down contaminants with the help of sound waves, electrically charged particles and changes in pressure. No waste is created in the process, because while the technology renders contaminants harmless it doesn't filter anything out. Another strong competitor for new business, according to Lux analyst Brent Giles, is Water Tectonics Inc., based in Everett, Wash. The company uses a process called electric coagulation, in which an electric charge forces contaminant particles into clumps that can be removed after they either rise to the surface of the water or sink to the bottom. The process avoids the use of chemicals, but it does produce waste that has to be disposed of. Another company, Altela Inc., based in Albuquerque, N.M., earned a spot on Artemis Project's 2011 list of the 50 most innovative water-technology companies in the U.S. Its technology mimics rainmaking. Wastewater is heated to the point of evaporation, which produces clean water in the form of vapor, leaving contaminant particles behind. The vapor is then condensed back into liquid form. The basic process, called thermal distillation, isn't new, but Altela has found a way to make it more efficient, by capturing the heat generated by condensation and using it for evaporation. Ned Godshall, the company's chief executive, says Altela's method uses a third of the energy typically required for conventional thermal distillation.

|

Do It Yourself

One potential drag on the use of all these technologies: Some drillers have started to simply reuse their wastewater without fully treating it. But it isn't clear how much of a factor that will be. Many technology companies and some researchers argue that there is a limit to such recycling because it doesn't clean the water enough for it to be used repeatedly and still be effective. The particles in dirty water can damage equipment and block the release of gas from the shale.

"When I learned in early 2010 that they were going to recycle, I thought they were going to do a real heavy-duty treatment" before reusing the water, says John Veil, who analyzed water treatment for the oil and gas industry for many years at the Argonne National Laboratory, and now does so at his own consulting firm. "They are not. All they are doing is getting out the big sand grains in a [filtering] process as simple as pouring the water through pantyhose."

Ms. Chernova is a special writer for Dow Jones VentureWire in New York. She can be reached at yuliya.chernova@dowjones.com.